San Cristóbal, Venezuela. How long does it take you to buy groceries? For Venezuelans, this has become a rather difficult question to answer. Nowadays, many medium and low-income citizens find themselves waiting for hours in order to buy rice, toilet paper and many other essential goods. And it does not stop with groceries; medicines, car parts, construction materials and even dog food are scarce ever since the Maduro administration’s concerted efforts to reduce production, including expropriating private business and establishing a heavy control over selling prices, met a steady decrease in oil revenue, the country’s main source of income.

While scarcity of goods is a common phenomenon across this South American country, San Cristóbal, the capital of the border state of Táchira, has been subjected to additional layers of purchase regulations and restrictions.

For many years, the Venezuelan government has shifted blame of scarcity of goods in Táchira, mainly fuel, onto contraband to neighboring Colombia. In reality, the government has implemented a heavy subsidy on fuel for decades, making it a valuable good for vehicle owners on the other side of the border. In their efforts to curve this flow, national and local officials have implemented a series of measures ranging from shortening the supply of fuel to Táchira to implementing filing quotas for state residents.

A similar scenario has extended to basic goods such as flour, sugar, butter, diapers, toilet paper and many more. Government’s heavy price regulation has made the selling of these goods on the other side of the border, at a much larger margin, a highly profitable endeavor for low-income citizens, distributors and, allegedly, even border patrol personnel.

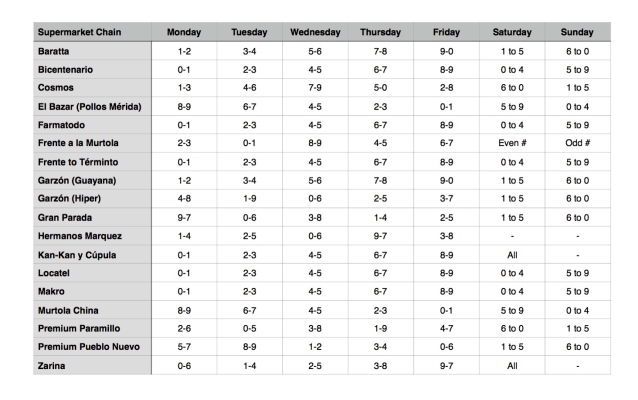

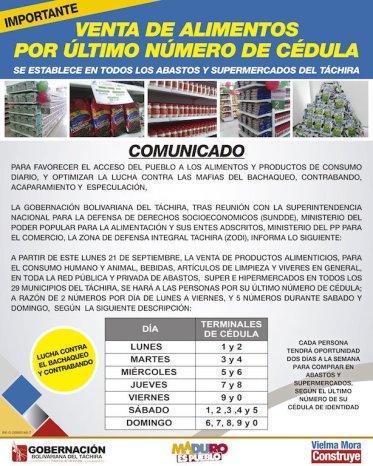

In view of dwindling popularity and parliamentary elections this year, the Maduro government has responded to this situation by aggressively shutting down the border with Colombia and by implementing a system of purchase control in Táchira, which includes allowing citizens to buy regulated goods on certain days of the week according to the ending of their Venezuelan ID.

On a given day, a person can visit an average of three stores on different parts of town and wait three or four hours in order to purchase, not what they may need, but rather random regulated goods available that day.

For a week, we embarked on this shopping journey and talked to Venezuelans in the long winding lines. Armed with a grocery list, 2,000 Bolivares (USD 317 in the official market) and a heavy coat of sunblock we started this excursion.

Tuesday

The first day we are alerted via text message that regulated goods arrived at Hiper Garzon, a local supermarket, and that there was no line. When we arrived at the front entrance we were instructed to go around to the freight entryway, where security allows in the people with the authorized ID terminal.

Once inside we are given a basket with two bags of sugar, one bottle of ketchup and three bars of soap: the first purchase of the day.

At noon we arrive at another Garzon store across town. In it, there is a familiar sighting: a long line out of the front entrance. The rumor is that they will be selling powdered milk. There are approximately 200 people waiting outside.

Powdered milk has become a coveted good ever since the national milk production has virtually disappeared as a result of nationalization and marginal production. Bottled milk is a rare find and when a jug is available it is generally a substitute called “milk beverage” which is a concoction of milk, milk-related products and water.

While we are waiting we speak to Esperanza*, 52, she tells us “This is the second supermarket I visit today. The line spread out over 4 blocks at the first one because there was rice, but as soon as I went in they ran out of it. They also had diapers but I don’t have any babies so I left. I hope I am able to score the milk here”.

She adds: “I work part-time so I am able to do this in the afternoons, but what is going to happen if the Governor changes that?”

This past week, Táchira’s Governor introduced an additional regulation extending the use of the ID terminal system to all supermarkets, whether large or small, and across the entire state.

This new regulation also implies that the ID terminal system will be unified, meaning that from Monday to Sunday a Táchira citizen will have access to regulated goods only twice a week, once during the working week and one on the weekends.

For citizens like Esperanza this is a problem. “If they are only allowing people to purchase the regulated goods twice a week, how are we supposed to run around town and wait 2-3 hours in each store and buy everything we need?” Adding, “I don’t have a car, I have to work in the mornings and I have to take care of my mom and my son. You tell me, how I am supposed to make it work?”

After waiting for two hours Esperanza is not allowed to buy the milk. The supermarket’s system reflects that she purchased milk last week so she has to wait an additional week in order to have the option to buy again. This temporary ban varies according to supermarket chain and it can go anywhere from 7 to 15 days, according to testimonies.

Many others are not able to purchase the milk either. As of today the store is selling regulated goods only to ID terminals 3 and 4 (instead of 1 and 9 as previously established), according to the Táchira Governor’s mandate.

As this change was made overnight in this chain, many found out at the register.

It is 3 pm and in our next supermarket stop there are approximately 300 people waiting outside the entrance. Under the scalding heat they are waiting for rice and powdered milk.

Yessica*, 24, has been waiting for the past hour in order to get in. She was able to buy rice earlier but as soon as she got out, workers were unloading the milk and she was instructed to go back to end of the line in order to be allowed to purchase it. She tells us that she left her infant daughter with her mom, who had the day off, adding “otherwise, I wouldn’t be able to buy anything or I had to bring her here but this is no place for a baby”. Many people in the line have their small children with them, some in their school uniforms, clearly annoyed at the long wait. Some, like their mothers and fathers are sunburnt.

Two hours later, Yessica is able to buy a bag (900g) of powdered milk and two of flour.

As we say goodbye, she gets on a packed bus for her hour-long trip back home.

Wednesday

Today, we head out to Cosmos supermarket. It is noon, and there are around 10 people waiting outside. The store is closed due to one of the weekly unannounced power outages that affect San Cristóbal which was, allegedly, caused by lack of maintenance of the electrical facilities. This one lasted “only” two hours.

At 1:30 there are around 150 people waiting. As a truck pulled over the store, people started approaching. As it has become customary, as soon as there are signs that regulated goods may be available, regardless of what they are, people will start to line up.

Today, the rumor is it that they are selling disposable razors and feminine pads.

Johan*, 34, says they are also selling diapers but he will not be able to buy them because he does not have his son’s birth certificate with him, a requirement for purchase. He says “thankfully my son is using one per day so one pack will last me until the end of the month”

A while later the store it is still closed because they are organizing the goods inside. Meanwhile, a store worker hands out numbered tickets to each one of the people in line; we are number 174. Soon after they open the doors and they allow in groups of 30 people at a time.

There is police personnel at the entrance which, according to the people waiting, means that there must be more goods than just only razors and feminine pads. Police enforcement is generally present when highly coveted goods such as milk and mayonnaise are being sold.

As people leave the store, their bags show the products that are available: detergent, shampoo, flour and milk. Excitement grows amongst the crowd.

Once inside there are three different spots in which goods are being distributed. On the west side: sugar, diapers and shampoo; on the east: flour, toilet paper and powdered milk, for which you have to show your numbered ticket and ID; and at the registers: detergent, razors and feminine pads.

Sebastián*, 26, is waiting in line to pay. He has one additional item in his cart: dog food. This product has become scarce as well and when available buyers have to present the pet’s up-to-date vaccination card and a veterinarian’s note of good health. Here, those requirements are not necessary.

Thursday

Today we head out to Hiper Garzon. Upon arrival we can see that there are around 900 people waiting in line, almost circling the supermarket’s extensive parking lot. People tell us there are a “myriad” of products available: toilet paper, pasta, all purpose flour and rice.

Miguel*, 44, says he is desperate for rice “ I haven’t been able to buy any in the last couple of weeks and we ran out of it”. Adding, “every time there is rice at a store it is not my turn to buy. So we now resorted to buying broken rice, you know? The one used to feed farm animals”

The possibility of buying regulated rice is exciting for most in the line. Being a scarce good, its price in the black market has soared to the beat of VEB 350, four times its regulated price.

Four and a half hours later, Miguel is able to buy the rice (two bags of 1 Kg. each), along with six rolls of toilet paper, two bags (1 Kg. each) of detergent, three packs of soap and two bags (1 Kg. each) of pasta.

Friday

On our last day shopping, we arrived at La Gran Parada supermarket. There is a line of approximately 600 people, extending three blocks outside the store. Glancing at people’s bags we can see that there is flour, mayonnaise, pasta and frozen chicken.

The line takes approximately two and a half hours. Inside, we talk to Lucía*, 56, who works in housekeeping. She hopes more goods will be released so she is extending her stay inside the store. She says “I only have today to do grocery shopping so I am waiting as long as I can”. She adds “I get paid per day of work and all that I earn I spend at the supermarket, and I am not even able to buy chicken, meats and vegetables”

For those unable to spend fourteen hours waiting in line to buy a fraction of the goods they need they resort to the black market where some of these goods, either individually or in “combos” are found at a much higher price tag. Facebook has become an accessible medium where goods can be purchased or traded, having specialized groups where many resort to these tactics to be able to take care of their needs.

During this week we saw Venezuelans experience a wide range of emotions. From excitement over the availability of goods, passing through their trademarked lighthearted humor, to frustration over how the decay of the industrial and large economic system has made way for a rampant government repression.

The restriction of Venezuelans’ freedom to choose has permeated daily life.

In a country where political dissent is punished, broadcast communications are controlled and the military are an extension of the Maduro administration, food control is another definitive step towards further human rights violations in this country.

At the time of this article’s publishing supermarkets have adopted the Governor’s mandate and residents are only able to buy regulated products twice a week.

A complete week in supermarket lines is now a bygone “privilege”.

Carlos Pérez Rojas.

* The names in this article have been changed in order to protect the identity of the interviewees.

** Monday was not recorded in our journey as there were not regulated goods being sold that day.

Very good article and very sad situation what Venezuelans have to deal with everyday. A situation unknown by most of the neighbors in the region.

LikeLike